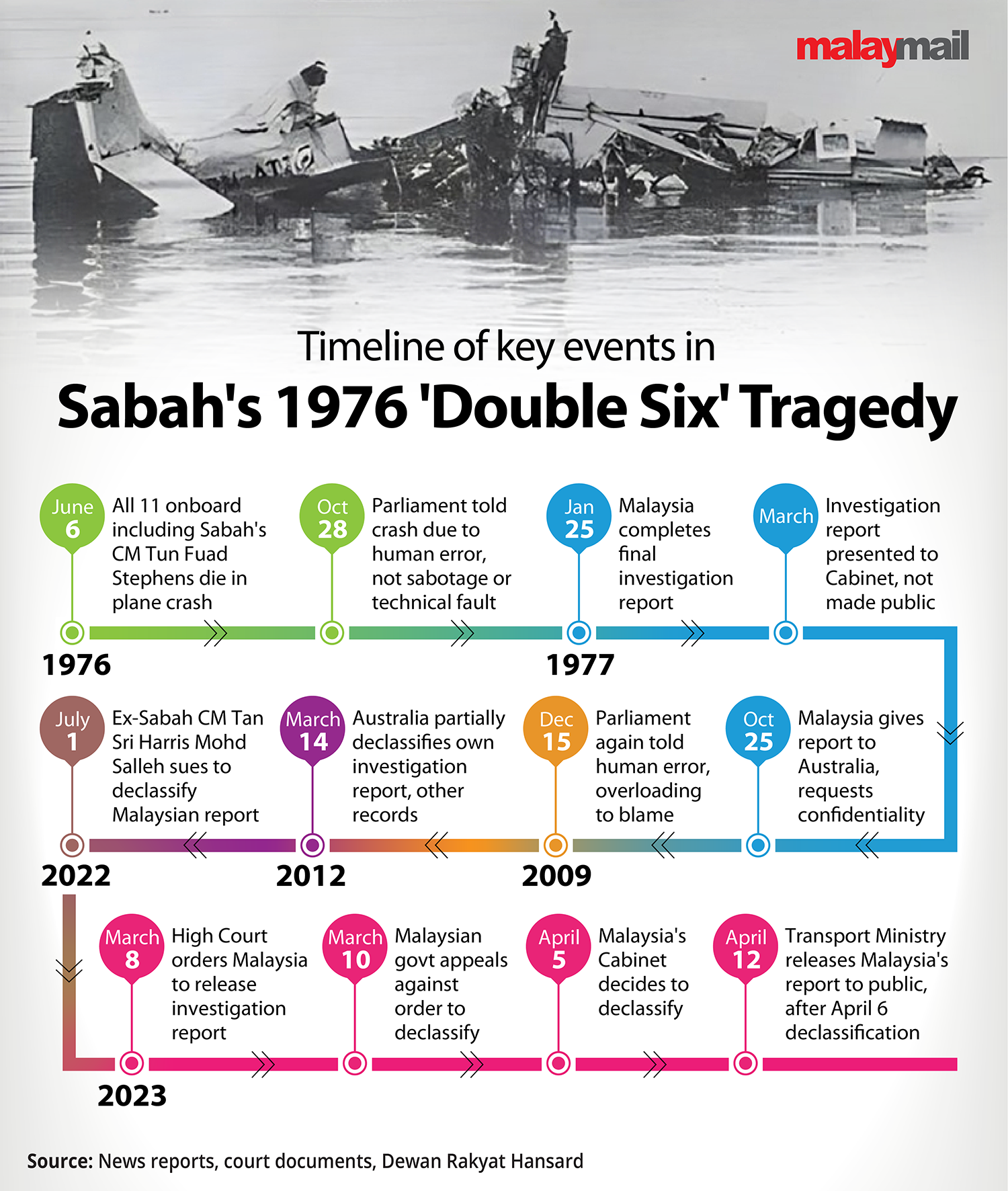

KUALA LUMPUR, April 26 — The Malaysian government finally declassified this month the 46-year-old report on the “Double Six” tragedy, releasing what investigators believed caused the air crash on June 6, 1976 that killed all 11 onboard including then Sabah chief minister Tun Fuad Stephens and key state leaders.

But were there clues all along? And why is Australia’s own investigation report on the plane crash classified? When will it be declassified?

Here’s what we know, based on Malaysia’s now-declassified 1977 investigation report, news reports and court documents sighted by Malay Mail:

1. The lawsuit that finally pushed the needle forward

Tan Sri Harris Mohd Salleh, who will turn 93 this year, was Sabah’s deputy chief minister at the time of the crash.

Harris became Sabah chief minister the day after the Double Six crash in 1976, continuing to hold the position until April 1985.

In court documents for a lawsuit he filed in July 2022 to seek for the Malaysian investigation report to be made public in order to clear his name, Harris said he has been accused since 1976 over the tragedy, with statements by politicians and the media implying he was somehow responsible.

“It has been regularly suggested that the Nomad Aircraft had crashed under suspicious circumstances, and that I had been involved in order to take over the office of the Chief Minister left vacant by the death of Tun Fuad Stephens,” he said, adding that it had also been insinuated that he was complicit in the purported assassination.

While Harris won in 2017 a defamation lawsuit against fellow Sabah politician Datuk Yong Teck Lee at the Federal Court, news reports on speculation over alleged foul play and conspiracy theories continued after that. This included allegations of an assassination plot against Sabah state government leaders and an alleged secret bid to seize Sabah’s oil and gas wealth.

Denying allegations that he was involved in causing the tragedy, Harris in his 2022 lawsuit referred to Sabah newspaper Daily Express’s June 27, 2021 report, where he said the crash was likely due to the pilot’s error on the baggage loading which caused the plane to be tail-heavy and unbalanced, or the design of the plane which had a history of crashes and pilot deaths.

Harris’s view was based on his own experience as a light aircraft pilot and the Malaysian government’s previous 1995 parliamentary response.

In one of his letters to the Malaysian government seeking for the investigation’s declassification before he filed the 2022 lawsuit, Harris said there have been 32 crashes with 76 fatalities involving the Nomad aircraft, and Australia’s production of this aircraft stopped in 1984 due to safety concerns.

2. The Malaysian government answers in Parliament: Human error, loading issues

On October 28, 1976, deputy communications minister Mohd Ali M. Shariff told Parliament he does not “plan” to present the “full report” on the aviation accident to the Dewan Rakyat, but went on to say: “However, the investigation carried out by an investigation team was of the view that accident is not from technical errors or due to any sabotage on it, but it was found to be due to ‘human error’.”

“According to that investigation, it was found that the loading space at the back of that aircraft had been loaded more than the maximum loading limit. With that, this resulted in loss of flight control on that aircraft when that aircraft was making preparations to land at the Kota Kinabalu Airport, which caused that accident to happen,” Mohd Ali said, without elaborating further.

He was replying to Kinta MP Ngan Siong Hing, who had asked if the Dewan Rakyat would be told the outcome of the crash’s investigation and whether it was due to sabotage or technical reasons.

On December 15, 2009 when Sepanggar MP Datuk Eric E. Majimbun asked for the probe outcome on the then 33-year-old tragedy, then deputy transport minister I Datuk Abdul Rahim Bakri said the concrete factors identified as causing the crash included “human error” or the pilot’s error, as well as overloading of the aircraft.

The deputy minister also told the Dewan Rakyat: “Although that aircraft only had capacity to carry six passengers only, it was boarded by 11 passengers along with excess baggage and this is believed to have caused the handling of the aircraft to be difficult and off balance, especially when landing, in addition to the lack of radar instruments then.”

Asked why safety was not prioritised when so many leaders were on the flight then, he said there might not have been monitoring or sufficient readiness to ensure safety then.

Abdul Rahim also told Parliament that VVIPs and VIPs were not encouraged to board the same aircraft or helicopters since the 1976 crash, but said this was also subject to the passengers’ own awareness.

On July 1, 2019, the Transport Ministry in a written parliamentary reply to Keningau MP Datuk Jeffrey Kitingan said the Malaysian government would study the proposal to declassify its report, and said it would provide notification about the decision and further action after obtaining the Cabinet’s agreement.

3. What Malaysia’s 1977 report said

Malaysia’s investigation report was completed on January 25, 1977 and presented to Tun Hussein Onn’s Cabinet in March 1977, but the results were never made public.

After Harris won a High Court order on March 8, 2023 for Malaysia to declassify the report within three months, the Malaysian government initially appealed against the order but on April 5 decided to declassify the report.

The transport minister declassified it under the Official Secrets Act on April 6, and put it online on April 12 — making it the first time it went public.

Here’s what the report said on the June 6, 1976 crash, where the sole pilot and all 10 passengers died when the plane went into a spin and nose-dived into the sea near the Kota Kinabalu airport.

The 10 passengers were the then Sabah chief minister and his eldest son and bodyguard, three Sabah state ministers (in charge of finance, local government and housing, works and communication), the Sabah deputy chief minister’s assistant minister, the private secretaries of the finance ministers for both Sabah and the federal government, and the director of Sabah’s economic planning unit.

The pilot: Citing available records, the report said the pilot has a history of poor performances in flying, with a marginal training record with the aviation company Penerbangan Sabah (known today as Sabah Air Aviation).

The pilot’s flying experience or total number of flight hours was approximated in the report based on available records, with the transfer of hours from his two previous flying log books — said to be burnt and stolen in 1969 and 1975 — not verified.

At the time of the flight, the pilot had the experience and a valid licence to fly this type of aircraft (Nomad N22B).

No evidence that the pilot was suffering from the effect of alcohol and drugs, he was reasonably fit.

But there was evidence to suggest he was tired, as calculations showed he would have exceeded the official duty hours of 10 hours — by 67 minutes — when the crash happened at 3.42pm. (His first flight of the day was at 6.35am from Labuan to Kota Kinabalu.)

There was evidence he had a mild stomach disorder from the previous evening’s food, as he had complained of being unwell before his 1.10pm Labuan-bound flight and before leaving at 3.09pm on the ill-fated flight to Kota Kinabalu.

The loading: The maximum take-off weight was 8,500 pounds (3.85 tonnes), and the calculated take-off weight was 8,065 pounds, which means the plane was loaded within its weight limit.

But the way the baggage was loaded or how weight was distributed caused the plane to be unbalanced and unstable, with overloading towards the tail.

From investigators’ calculations and recovery efforts, 177 pounds of baggage were found in the front baggage compartment (which had a maximum 400 pounds weight limit), while an estimated 325 pounds of baggage in the rear baggage compartment exceeded its maximum 198 pounds weight limit. A further 90 pounds of personal effects were distributed throughout the cabin.

The pilot had loaded some baggage into the nose baggage compartment, while an accompanying pilot — who was later bumped off the flight to accommodate a 10th passenger for the nine-passenger plane — was instructed to load the rest of the baggage into the rear baggage compartment.

The report suggested it was possible that the pilot was oblivious to the fact that the loading was incorrectly distributed.

“Against this backdrop with VIP passengers boarding the aircraft and many other people evidently standing around it is possible that the pilot was not in control of the loading. It is, of course, not known what pressures were on the pilot with such important passengers, to get on with the flight.”

Baggage belonging to some passengers of another Kota Kinabalu-bound flight were later discovered to have been loaded on the aircraft, based on what was found at the wreckage.

The plane: No flight recorder was installed on the plane, there was no requirement to fit one. No evidence to suggest the aircraft or its systems had failed before the accident. No evidence that any precrash defect or malfunction of the aircraft or its engines was a causal factor; the aircraft had been maintained according to schedule.

The plane was damaged beyond repair and destroyed from impact with the sea and salt water.

Everything else: No evidence that weather conditions contributed to the accident. “There was no evidence of sabotage, fire or explosion”. Procedures not followed by pilot and flight company, such as: Load sheet not prepared, passenger manifest not completed, instrument flight rules (IFR) flight plan not filed as required for VIP flights, monitoring how long pilot had been on duty not done.

Conclusion: In simple language, the probable cause of the crash was the plane being off balance, which resulted in the pilot losing control of the aircraft while preparing to land.

Recommendations: Penerbangan Sabah did not apply or get approval to fly the new aircraft type (Nomad N22B) before starting such flights, recommendation is for all public transport operators to have such approval before starting operations on new aircraft types.

Also recommended to limit Penerbangan Sabah to operating aircraft with a lower maximum weight limit of 6,000 pounds until it improves operations and procedures to the Civil Aviation Department’s satisfaction, and to issue a circular to all operators and pilots on the importance of compliance with procedures before any flight.

The full 21-page report — which said this was “not a survivable accident” — can be accessed here.

The report was prepared by a seven-member team, with its members being from the Civil Aviation Department, the Royal Malaysian Air Force and two representatives from Australia’s Department of Transport.

So yes, the declassified report does match what the Malaysian government has been saying in Parliament since 1976.

4. Why did Australia also classify its own investigation report?

The Australian state-owned Government Aircraft Factories (GAF), which manufactured the Nomad aircraft in the “Double Six” tragedy, also carried out its own investigation and prepared a report which was not made public. GAF’s chief test pilot and chief designer had acted as technical advisers to help the seven-member team in Malaysia’s investigation.

Malaysia in 1977 asked Australia to keep the investigation details confidential.

On March 14, 2012, the National Archives of Australia (NAA) decided to only publish five pages (including one page which had redacted information and with the NAA uncertain where the obscured information can be located) from the 50-folio or 50-page report by GAF’s investigation team. (This is the NAA’s record series B5535.)

The two main reasons for the NAA’s decision to withhold the remaining 45 pages of the Australian report were: the public disclosure of such information could cause damage to international ties with the current government of a foreign country; and that disclosure of information received confidentially from a foreign government would amount to a breach of confidence owed to that foreign government.

In deciding in 2012 not to fully declassify Australia’s report as it could damage ties, NAA said Malaysia had yet to publicly release its investigation report, and said international convention requires the participating state (Australia) not to release investigation details “without permission” from the main investigating state (Malaysia).

As for why fully disclosing Australia’s report could be a breach of confidence owed to Malaysia, the NAA said Malaysia had provided confidential information to Australia with the expectation that it would not be released to the public and that information “is still regarded as sensitive”.

“The information is still accorded security protection by the foreign government and it has asked that the information not be disclosed to the public,” the NAA said.

Also on March 14, 2012, the NAA decided to partially release (including 14 pages with redacted information) another set of records totalling 96 pages on the “Double Six” crash, and keeping 48 pages or over half of the records fully classified, citing similar reasons of possible damage to international ties. (This is the NAA’s record series B638).

On August 10, 2021, Australia’s attorney general Michaelia Cash replied to Sabah’s Dewan Negara lawmaker Datuk Theodore Douglas Lind’s request for her to intervene and have NAA declassify the GAF report, saying she could not intervene as the NAA independently makes such decisions under Australian laws while also noting NAA’s obligation not to release information which requires continued protection.

In a May 12, 2022 letter, Harris through his Australia lawyers applied to the NAA to ask for full unredacted access to the two sets of documents. This letter said Malaysia had on October 25, 1977 given Australia a copy of the final report on the investigation with the request for it to be treated as confidential.

On July 26, 2022, the NAA maintained its 2012 decision not to declassify the 45 pages in the GAF’s investigation report, stating similar reasons for not disclosing “sensitive” information.

Separately, on June 21, 2022, Australia’s Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications replied to Harris’s request for the Australian investigation report to be released, stating that transport accident investigator Australian Transport Safety Bureau has said the report is a “technical aircraft examination conducted in support of the Malaysian government’s investigation”.

The Australian department also said that “Australian officials will engage relevant authorities in Malaysia to seek views on releasing relevant information”, in line with an international convention.

On January 23, 2023, the NAA updated Harris’s lawyers on his May 2022 application, saying that it proposed to maintain its 2012 decision on the GAF’s investigation report (B5535) and maintained its 2012 decision to only partially release the separate set of documents (B638). Similar reasons were cited, with NAA highlighting Malaysia’s 1977 request to keep the report confidential and that Malaysia has yet to publicly release any report.

5. What’s next?

On April 13, Malaysia’s current transport minister, Anthony Loke, said Australia was prepared to release its own report, but had asked Malaysia for its opinion and approval out of respect as the accident happened in Malaysia.

“As far as we are concerned, we have no objection, so it’s up to the Australian government when to release the report,” Loke said, just a day after Malaysia released its own report.

Also on April 13, Australian High Commissioner to Malaysia Justin Lee said the Australian government has been working closely with Malaysia to release reports on the 1976 crash, and that Australia is “currently working through a domestic legal process to release the Australian records”, Malaysian news outlet The Star reported.

Harris had continued to pursue the full declassification of Australia’s investigation reports on the “Double Six” crash, and had applied to the Australia’s Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) for a review of the NAA’s decision to disallow full access to the documents.

When contacted, Harris’s lawyer Jordan Kong told Malay Mail that the Australian government had proposed to settle the matter after hearing that the Malaysian government was disclosing its report.

The terms which were proposed by Australia and agreed to by Harris are exactly the same terms contained in the AAT’s April 24 decision.

In its April 24 decision, the AAT decided to provide full access to the two sets of documents (B5335 or “GAF37: G Bennett — Sabah Air Nomad — report by Government Aircraft Factories (GAF) Investigation Team on a crash of Nomad Aircraft in Malaysia 9M-ATZ on 6 June 1976”, and Part 1 and Part 2 of B638 or “Accident Malaysian Nomad Aircraft 9M-ATZ on 6 June 1976”).

Harris’ lawyers told Malay Mail that Australia will directly release the documents to them and that they will make these reports available to the public.